How Much Surplus Labor Do We Have?

By Peter Coy and Matthew Philips

August 21, 2014 - Businessweek

Janet Yellen wants the hawks in the Federal Reserve System to cut her some

slack on the topic of slack. As economists use the term, slack in the job market

is a measure of labor supply. Too much slack means high unemployment. Too little

means worker shortages, spiking wages, and inflation. Whether therefs too much

slack, too little, or just the right amount has been a topic of intense debate

since well before Yellenfs scheduled Aug. 22 speech on labor markets at the

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas Cityfs annual conference in Jackson Hole,

Wyo.

Yellen, in her first year as chair of the Fedfs board of governors, is a

slacker—she says the labor market remains soft and the central bank should keep

concentrating on growth, not restraining inflation. Shefs up against a group of

hawks such as Charles Plosser, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of

Philadelphia, who say the slack is all but used up. Both sides cite official

statistics to make their cases. gTherefs lots of asymmetry out there in the data

right now,h says Neil Dutta, head of U.S. economics at Renaissance Macro

Research.

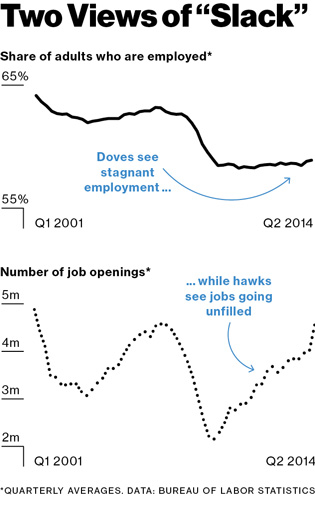

Doves on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) play down the

falling unemployment rate (6.2 percent in July) because, as they point out,

it counts only people who are actively seeking work. The 2007-09 recession was

so deep that many people stopped looking. Employment as a share of the adult

population remains depressed. The dovish theory is that if demand heats up, many

of those people will be drawn back into the workforce.

Easy-money advocates point to the high number of people—7.5 million—who

want full-time jobs but are working part-time for economic reasons like

gunfavorable business conditions.h Before the recession began, there were only

4.6 million people in that situation. In a recent speech, Minneapolis Fed

President Narayana Kocherlakota cited involuntary part-timers as evidence that

plenty of workers are on the sidelines, ready to fill increased demand for

labor.

The Fed chair has managed to keep most of the FOMC on her side. After its

latest meeting on July 30, the committee said in a statement that ga range

of labor market indicators suggests that there remains significant

underutilization of labor resources.h All of the Fed governors in Washington

lean dovish, as do presidents of the regional banks in New York, Chicago,

Boston, and San Francisco, not to mention Kocherlakota.

But Yellen canft take support for granted. Philadelphiafs Plosser dissented

from the July 30 statement on the grounds that the language about how long

interest rates will be kept low gdoes not reflect the considerable economic

progress that has been made toward the Committeefs goals.h Minutes released on

Aug. 20 revealed some sympathy for that view among other FOMC members.

Besides Plosser, the hawks include the Fed presidents in Richmond, St. Louis,

and Dallas. (Not all regional presidents vote in any given year, though all

participate in FOMC deliberations.) Hawks focus on the sharp increase in the

number of unfilled jobs, asking how much slack there could truly be in the labor

market if there were 4.7 million openings for workers at the end of June.

Thatfs up from a low of 2.1 million in July 2009. They are concerned that

many people who dropped out of the labor market are never coming back—because

they retired early or went on disability, or their skills atrophied. Declining

unemployment could soon switch from a good thing to a bad thing, they suggest.

In a recent speech, Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher said, gThe economy is

reaching our desired destination faster than we imagined.h

To Yellenfs credit, an inflationary spike in wages is nowhere in sight. Given

current inflation and productivity growth, workers should see wage gains above

3 percent, says Ethan Harris, co-head of global economics research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch

(BAC). Wage growth has been closer to

2 percent, no higher than overall inflation. Itfs possible, as the hawks

worry, that wage pressure is building up unnoticed. But Yellen has said that a

little bit of above-target wage growth is OK as long as the public continues to

believe that inflation will remain low over the long term. For now, the slackers

at the Fed are running the show.